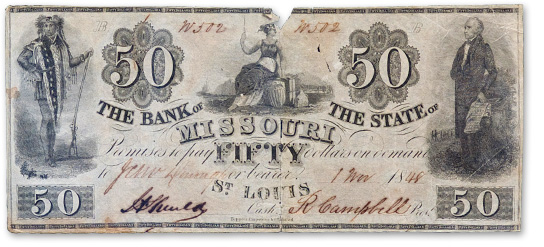

Circa 1848

America

Paper and ink: 7 inches by 3 inches

Campbell House Museum

Descriptive Detail

To the left, clad in an elaborate headdress and coat, fingers holding a rifle tip in walking-stick fashion is Meriwether Lewis, and on the right, holding a letter and a briefcase, is senator Thomas Hart Benton. Each engraved vignette symbolizing connections to local history. The number “50” appears boldly in four places. In the center beneath a version of “lady liberty” is the word “Missouri.” The assemblage of images, words and numbers indicate it is a certificate of legal tender from the Missouri State Bank. The date “1 Nov. 1848” and “R. Campbell” in well-formed script is at the bottom. These bank notes were accepted in many places throughout the West because the Missouri State Bank had a reputation for stability—Robert Campbell, as bank president, hand-signed each of them. It would be difficult for the public to know this one was counterfeit. When the counterfeiting was discovered, all $50 bank notes were recalled.

Local Historical Connections

When Robert Campbell first arrived in St. Louis, it was emerging from a time when currency was measured in reference to the French “livre” evaluated at 17 ½ cents. “Fur money” was the real money. Stacks of pelts, weighed and tabulated in livres, were exchanged for notes of credit that passed from one merchant to the next—transactions extended as far as New Orleans and Canada. This form of credit was used in much the same way as credit cards are today. The first bank note issued in St. Louis in 1817 had an image of a beaver in a trap on it. As a trapper, businessman, and entrepreneur, Campbell’s enterprises grew within this evolving economic system. As his wealth increased, so did his direct involvement in finance. By the 1840s he was heavily involved in banking systems and investments—the dollars issued from this bank were considered as good as gold. Campbell’s signature appeared on all bank notes. He also served as a “personal banker” at times, setting up accounts for “women of color” who had little access to banks.

National Historical Connections

In the early part of the nineteenth century, coins from France, England, Germany, Italy, and the Mexican peso were popular circulating along with money issued in this country. Even though bills were produced at the treasury in New Orleans, most were passed in commerce to the East and South. Individual and state banks gradually emerged and not only co-existed with a federal system, but these local banks were frequently favored. When the second charter for a centralized Bank of the U.S. expired in 1836, the Congress defeated its renewal. Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a staunch supporter of Missouri statehood a few years earlier, sided with President Andrew Jackson to defeat a central banking system, proclaiming need for money to “put the wheels of business in motion.” For close to thirty years following this, state-chartered banks and un-chartered or “free banks” issued their own money—there was little oversight. By 1860 there were more than ten thousand different bank notes in circulation. Financial instability was increasing. The passage of the National Currency Act of 1863 was the beginning of standardized currency and a unified central banking system in the United States.

top^

next artifact}

|

|